STOLPERSTEINE GELSENKIRCHEN

Ausgrenzung erinnern

← Home

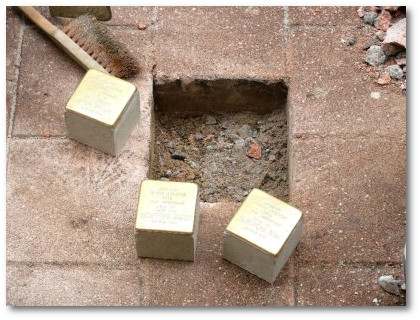

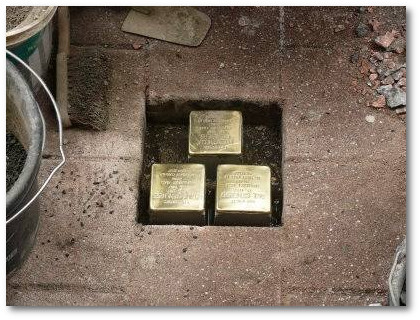

Stumbling Stones - Stolpersteine

|

They are just four inches square and often obscured by the dirt and dust of urban life. But the'stumble stones' implanted into the cities and towns of Germany punch far above their weight in terms of human emotion. With over 27,000 of them across the country and Europe, these tiny brass tablets of information about the targets of the Nazi Holocaust have become the most potent reminders that the victims were humans and not abstract historial statistics. Artist Gunter Demnig's 'stumble stones' tell the casual walker that in the house he or she is standing outside once lived people who were rounded up and taken away to be murdered because of their ethnicity, religion, politics or sexual persuasion.

|

|

And although small, they have collectively become the single biggest Holocaust memorial in Germany over the past 15 years. "Here lived" begins the inscriptions engraved on every one. And when the information is imparted, be it outside a crumbling tenement or a newly yuppified apartment block, the connection with those dark days when people were stolen in the night is immediate and powerful. "The stumbling blocks become reminders and voices; they call out, ‘Every human being has a name,’" says Miriam Gillis-Carlebach, daughter of Hamburg’s last rabbi, who commissioned stones from the artist for family members deported from the port metropolis to their deaths.

|

|

Demnig has placed stumbling stones in about 600 cities, towns, and villages throughout Germany and Europe; there are more than 27,000 so far. Installed without fanfare, they were recognised this week in Germany by victim's groups as the single most moving reminder of the terror of the Third Reich. "It is for all the victims," says Demnig, "Jews, gypsies, homosexuals, politically persecuted, handicapped, resistance fighters and Jehova's Witnesses." Demnig was born in Berlin but his home and his studio are in Cologne: the Rhineland city that was enthusiastic in its support for the Nazis. In 1990, he marked in chalk the route taken by Cologne’s gypsies when they were deported in 1940. When he retraced the signs three years later, it was the the reactions of an older woman gave him the idea for the stumbling stone project. "There were no gypsies in our neighborhood," Demnig says she told him. “She just didn’t know that they had been her neighbors, and I wanted to change that. "I designed the stumble stones to bring back the names of Holocaust victims to where they had lived; in my opinion, existing memorials have failed to do that. Once a year, some official lays a wreath, but the average citizen can avoid the site very easily."

|

|

The stumble stone, unless one is plans minutely the route of every walk, allows for no such moral shirking: they seem to be everywhere in big cities now. One literally does stumble across them At Max-Planck Elementary School in Berlin, a class started one of many projects inspired by Deming. To prepare for the installation of the stumbling blocks, students researched archives, talked with historians, and interviewed survivors and their families to learn about that time.

|

|

"Behind the facts, there are numerous fates and tragedies that can touch you and make history come alive," explains teacher Christoph Hummel. There is opposition - cities such as Munich and Leipzig don’t allow the stones, claiming that they don't want their sidewalks "defaced," or that there are enough memorials to the murdered already.

|

|

Sometimes in places where they are in profusion homeowners will argue against having them on their doorstep. But the project rolls on. "It has become an avalache: Every day we have requests for stumbling blocks", says Uta Franke, Demnig’s project coordinator. "In many cities, towns and even villages, just the idea to set a stone starts a new wave of discussion and research about the Nazi past.I know I can’t do six million stones, but if I can inspire a discussion with just one, something very important has been achieved," said Demnig. A few stumble stones have been wrenched from the ground by neo-Nazis.

|

|

Others have been defaced with swastikas. There are still a few places in Germany where ultra-right sentiment burns fiercely enough among locals that Demnig can go about his work only with a police escort. "Those are police rules, not my rules," he stressed. "I personally don't feel in danger." Demnig is driven by artistic vision, he said, not by any sense of historic guilt or remorse as a German. "There were no victims in my family, but also there were no culprits," he said, noting that his father, like most men at the time, served in the regular German Army during the war but was not involved with the SS or Gestapo, the twin instruments of Nazi terror. "This is my life's work. I will continue for as long as I'm able," Demnig said. "Giving names back to the dead is a way of keeping them alive."

|

For those who are interested getting in touch with Stumbling Stones - Stolpersteine in Gelsenkirchen,

please email → Andreas Jordan

Project Group STOLPERSTEINE Gelsenkirchen, Januar 2011

|

↑ Top

|

|