|

IN MEMORY OF VICTIMS OF FORCED LABOUR 1940-1945

EXHAUSTED AND EXPLOITED IN NS WAR ECONOMY

PRISON OF THE GELSENKIRCHEN-BUER POLICE STATION

WHERE MANY NAMELESS PERSONS STARTED THEIR WALK

TO BE EXECUTED

|

Installation address: Kurt-Schumacher-Straße/Hölscherstraße (police headquarters, date of installation 23rd May, 2019)

STUMBLING BLOCK REMINDS OF THE INJUSTICE SO MANY VICTIMS HAD TO SUFFER AND THE AGONY THEY HAD TO SUSTAIN

Fig. 1: female forced workers from the Soviet union had to wear a blue, rectangular patch with the white inscription OST (=East).

„Stumbling blocks“ (brass plates fitted with names of victims) are a special form of the „stumbling stones“ (memorial stones). They are designed and installed by the sculptor Gunter Demnig. Whereas each stumbling stone is dedicated to an individual, a stumbling block reminds of groups of victims and sites where injustice took place. Thus the stumbling block in Gelsenkirchen will be installed symbolically in memory of more than 40,000 men, women and children originating from both, Eastern and Western parts of Europe, exploited as ill-paid forced labourers in the German wartime economy and armaments industry between 1940 and 1945, be it as civilians or prisoners of war. The text on the plate will also commemorate the nameless forced labourers whose way to their execution started from the police prison, according to current state of research. And nameless they will stay due to the lack of records regarding their identities.

In fulfillment of forced labour arrangements with industry, administration, trading companies, manufacuring trade, private households, catering- as well as with the farming industry , all those people who had been displaced to Gelsenkirchen were deprived of their rights, humiliated, assaulted and exploited. The Nazi regime avoided to use the term „forced labourers“; instead they called them „ausländische Arbeitskräfte“ (foreign labour force) in officialese. Often enough the term „foreign person“ is used in decrees. Locally speeking, the employment office of Gelsenkirchen, the „Arbeitsamt“ was in charge of the so-called „Arbeitseinsatz“ (deployment of labour) – meaning the request and distribution of the forced labourers regarding the diverse labours squads and assignment sites in so-called „kriegswichtigen Betrieben“ (factories and companies vital to the war effort). Whoever wanted to employ forced labourers had to contact the „Arbeitsamt“. Depending on the division of labour, either the „Arbeitsamt“, „Deutsche Arbeitsfront“ or the labour inspectorate were in charge. Big enterprises as well as smaller companies such as handicraft businesses, local authorities and administrations but also farmers and private households requested more and more foreign labourers hence why they all are to be held responsible for the system of forced labour.

The manufacturing industry benefited from the considerable expansion of their production – only achieved by the usage of forced labourers. German employees were promoted to the position of foremen , thus getting higher wages. Consequently, unnumerable „Volksgenossen“ („national comrades“ ) profited from the system of forced and bonded labour – not only the fascistic state and its municipalities. It was not necessary to be a distinct Nazi to benefit from regulations in the Third Reich.

|

"Forced labour was omnipresent. Forced labour was a mass phenomenon and could not remain undetected to any German."

|

Many Germans regarded the male and female forced labourers as seasonal workers similar to those they knew from pre-war times. The mainstream of the German society at that time would use the terms foreign or guest workers as well as „Ost or Westarbeiter“ meaning workers coming from the East or West instead of forced labourers. Often enough, the population did not take notice of the tightly guarded crews of exhausted and wretched people, when they were driven through the streets to the places where they had to work. Mainly during the last two years of the war, they were present in the streets of the cities on their way to and on their way back from work into the camps and dwellings. Postwar times were characterized by a collective social repression, and forced labour was a taboo subject, and so these poor people were forgotten.

|

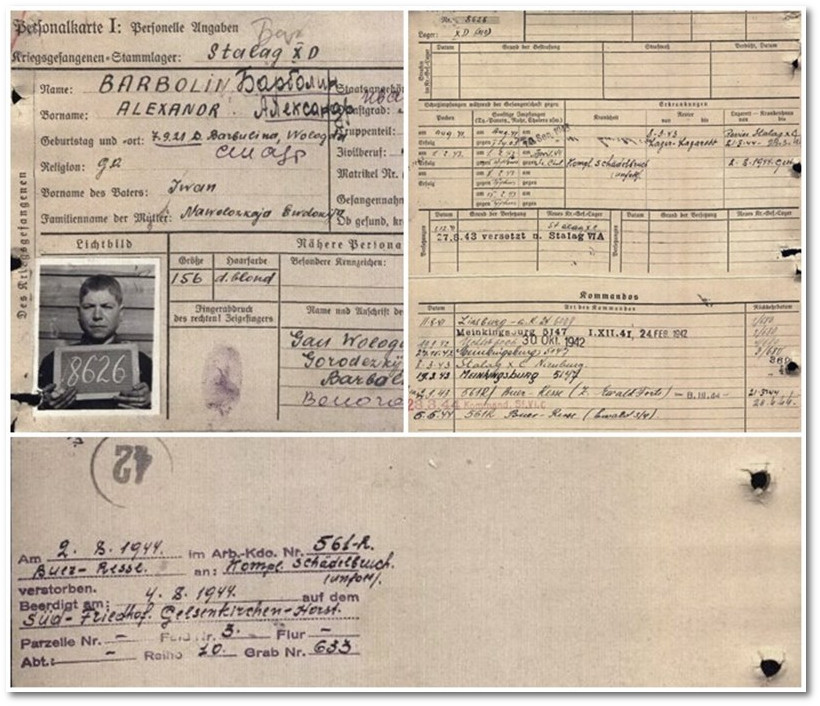

Fig.: workpass of Alexandr Barbolin, Russian forced labourer, latest labour squad 561R, Buer-Resse, Ewald ¾, deceased on 02nd August, 1944, cause of death: cpl. Skull fracture (accident) – the fatal accident is explicitely pointed out. (Card: Obd memorial)

More than 3,500 forced labourers died from „work accidents“ between 1940 and 1945, of cruelty, by targeted killing, as well as from starvation and insufficient medical care. For reasons that can only be called racist, forced labourers, prisoners of war and other groups banned from the fascistic „national community“ were excluded from the anti-aircraft protection facilities meaning they were not permitted to seek shelter during air attacks. Nearly forgotten graves of numerous prisoners of war and forced labourers can be found on the Gelsenkirchen „Hauptfriedhof“ (central cemetery) as well as on most other cemeteries in and around Gelsenkirchen. Permanent sites of mostly nameless victims. The majority of them came from Russia. In most cases they were or still are believed to be lost or missing by their relatives. And often enough injustice was done to them again by historical reports, local and non-local, adopting the perpetrators' claim that the victims were plunderers or criminals, justifying their criminal deeds.

|

|

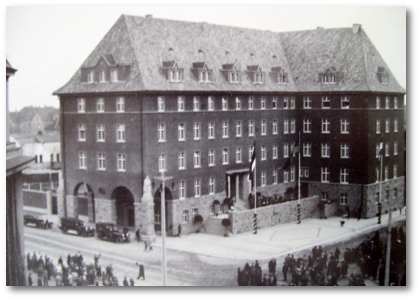

Fig.2 :The main police station in Gelsenkirchen, inaugurated in 1927, one of the many places of mischief and injustice during the fascistic tyranny between 1933 and 1945. There was a fully guarded police station in the semi-basement ,accessible from Gelsenkirchener Straße (today: Kurt-Schumacher-Straße). In addition to that there was a prison with 8 solitary cells and 2 collective cells, accessible from the courtyard as well as a flat for the prison officer.

Especially in the final stage of the war foreign forced labourers were considered as a threat, above all by the police authorities. „In the final phase of the war the principle of danger defence by means of an aggravation and brutalization of all measures against forced workers serving as a deterrent became the action-guiding standard of police work as far as undesirable aliens were concerned.“

The outcome of all this are assaults of violence and battery against concentration camp prisoners and forced labourers but also against their own „Volksgenossen“, soldiers and civilians who do not believe in the ultimate victory („Endsieg“) propaganda.

Fig.: NS place of injustice, the police head office Gelsenkirchen-Buer, back view. The prison in the semi-basement of the building was situate behind the wall (centre of picture)

Prison of the police station Gelsenkirchen-Buer

The prison in the building of the police station Gelsenkirchen-Buer, Adolf-Hitler-Platz 4, was subordinate to the 13th police station Buer-Mitte (Buer Central). In 1938 a policeman of the 13th police station, police officer Alois Tappe, became prison warder. For many forced labourers and other NS dissidents the police prison stood at the beginning on their way to their execution. In his interrogation as a prison warder officer Tappe described the prison situation as follows: when he was in charge, the monthly average occupancy was 25-30 persons. By the end of 1944 the number of detainees increased to 45 on average. New entries and leavings were exclusively under the command of Gestapo and the CID (criminal investigation police). In the last year of the war, Gestapo more frequently collected groups of 10-15 people from the prison and took them away by car. He had no knowledge about their destination. He was aware, though, about the methods of Gestapo. Around beginning of January, 1945 Revierhauptwachmeister (chief police officer) Vitus Michel became head of the 13th police station. He appointed constable Christoph as successor of Alois Tappe, who had been subject to the suspect of negligence thus paving the way for some escapes.

|

The cruelty of the Nazi regime could no longer be concealed. Crimes and offences against prisoners and foreign forced labourers commited by the Gestapo replicated the murderous crimes and homicidal methods of the NS task forces and police battallions in the East – henceforward in the „Reich“ itself. It did no longer happen far away offside the daily life of most Germans – in the far distance at the front lines or hidden behind fences and walls of the concentration and extermination camps – but in the midst of and in front of the eyes of the German citizens, in the public, in front of the „doorstep of society“. Especially during the last few months of World War II there were mass executions in Gel- senkirchen against the background of the „Spezial- behandlung“(= euphem. special treatment) of the so-called „Ostarbeitern“ (forced labourers from East Europe) by the police, as well as spontaneous acts of violence against forced workers.

|

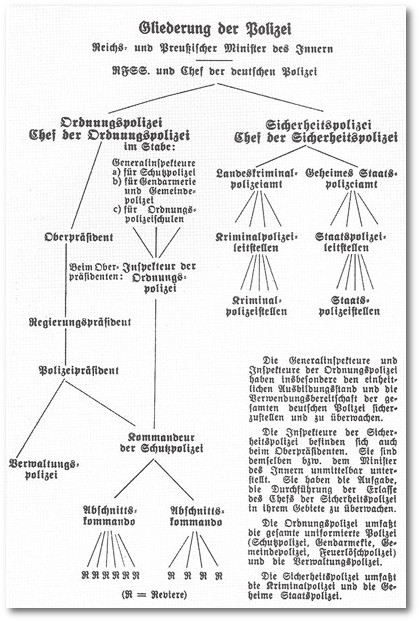

Fig. 3: structure of the police from 1940. During the last few years of World War „ the Geheime Staatspolizei (Gestapo)“ and the „Kriminalpolizei (Kripo)“ became more and more the instrument of terror (click for magnification).

Especially during the last few months of World War II there were mass executions in Gelsenkirchen against the background of the „Spezialbehandlung“(= euphem. special treatment) of the so-called „Ostarbeitern“ (forced labourers from East Europe) by the police, as well as spontaneous acts of violence against forced workers.

In the mining industry of the Ruhr (Ruhrbergbau) many a homicide committed by a foreman or a simple pitman underground was declared as a“work accident“. Very often, the dead bodies just stayed underground. The main accusation against the forced labourers working in factories and workshops was sabotage, outside the working places the main reason was plundering. But in order to hang a forced labourer, Gestapo murderers did not need a proof of an actual offence - a suspect as such was sufficient for death penalty.

Not only the Gestapo but all other divisions of the German police took part in the fascistic terror, in the German Reich and in all occupied territories. All forced labourers from the East were subject to a specifically created penal law, also providing for extrajudicial executions. Euphemistically, the Nazis called this procedure „Sonderbehandlung“ (special treatment).

The police captured the forced workers in their countries of origin and watched them inside the territory of the German Reich. By means of decrees and remissions the Gestapo ruled the working and living conditions of the forced workers as well as their contact to the German population. Workers coming from Poland and the Soviet Union suffered from the severest discrimination as well as members of the Red Army, from late autumn 1943 onwards also the Italian prisoners of war. The description „ Italian military detained persons“ for this group was also an invention of the Nazis in order to detract the Italians from the protectional mechanisms of the Geneva convention. In 1944, most of them were declared civil workers.

Besides the concentration camp prisoners, foreign forced labourers formed a large group of victims suffering from the unrestrained violence and brute force applied against them during the last months of the war. They were considered as extremely dangerous, as the „interior enemy“. Their quantity alone stirs the general concern in Germany, that with the allied troops coming closer, they could no longer stay under control: 12 million „foreign labourers“ (as per official Nazi nomenclature) were forced to toil for the war industry on the territory of the German Reich.

An agreement between the last Lord Chancellor of the Reich Thierack and Reichsführer SS Himmler dating back to 1942 endorsed by Hitler formed the basis for the application of the so-called „special treatment“ which meant nothing else but „execution“ in the language use of the Nazis. Neither Poles nor other members of East European countries („Ostvölker“) were entitled to get a due process of law. Their sentence was supposed to be a purely administrative measure and was passed only by the police. This agreement was communicated to all police stations by the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA) in Berlin. Reichsführer SS Himmler, who was also the head of the police, governed and coordinated its performance by means of a decree in January 1943. According to the decree the „Staatspolizeileitstelle“ had to apply for the „Sonderbehandlung“ at the „Reichssicherheitshauptamt“ , indicating all personal data of the accused as well as the criminal charge. The instruction for an execution would then be issued by express letter or telefax. Signature and thereby approval was given by the head of dept. V in the RSHA or a subordinate person designated by the former.

At first, executions were supposed to take place in the nearest concentration camps. Between 1942 and March 1943 the independent cc Niedernhagen adjacent to Paderborn for example served as a place of execution for the the headquarters (Leitstellen) of the Stapo (Staatspolizei) in the districts of Westphalia and Lippe. However, in the face of the amount of forced labourers deployed in the last years of the war executions were to an increasing extent ordered to take place outside these camps. For intimidation reasons executions were often carried out in the presence of other workers from the East. These secret decrees were more and more extended to foreign workers of other nationalities, and in the final phase of the war they were also directed against Germans. The implementing regulation of the decree from 1943 had already included special instructions for the „special treatment of Germans“. In the final phase of the war the Gestapo toughened up the terror against the own population considerably. Executions were deliberately performed in public in order to scare off the war-weary population and avoid an early capitulation. Mainly forced labourers and war prisoners were among the victims of the excesses of murder and executions in the last few months of the war. Gestapo murdered a great many prisoners and threatened all those who were not prepared to follow the regime until its fall with death.

|

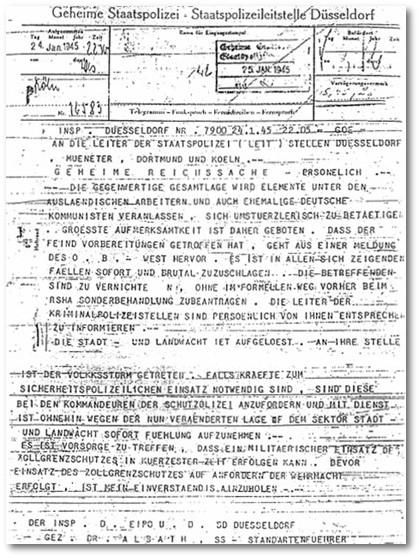

Fig.4: Telex Dr. WalterAlbath (SS Standartenführer and Inspekteur of Sicherheitspolizei and SD in Wehrkreis VI = SS regiment leader and inspector of Security Police in Wehrkreis VI, starting from 14th Jan., 1945 head of Stapo headquarters in Düsseldorf, Münster, Dortmund and Cologne: „ (…)

In all emerging cases the order is to take immediate action without mercy. The persons concerned are to be destroyed., without prior application for special treatment to RSHA. Heads of criminal police stations are to be informed in person.(click for magnification).

Fig.4: Telex Dr. WalterAlbath (SS Standartenführer and Inspekteur of Sicherheitspolizei and SD in Wehrkreis VI = SS regiment leader and inspector of Security Police in Wehrkreis VI, starting from 14th Jan., 1945 head of Stapo headquarters in Düsseldorf, Münster, Dortmund and Cologne: „ (…)

In all emerging cases the order is to take immediate action without mercy. The persons concerned are to be destroyed., without prior application for special treatment to RSHA. Heads of criminal police stations are to be informed in person.(click for magnification).

On 26th January, 1945 Dr. Albath gave order in a letter addressed to the head of the headquarters of the STAPO in Düsseldorf, Münster, Dortmund and Cologne that all „special treatments“ could „from now on be applied without any prior permit from the RSHA (Reichssicherheitshauptamts)“. In those cases RSHA could be informed retrospectively. „In the event that a great many cases are concerned , public special treatments will not be adequate for all of them. For all other cases, special treatment can be applied tacidly, also by means of shootings. You are requested to refrain from applications to the RSHA regarding special treatments in concentration camps. This request does not allow any exception. If the case arises that a special treatment would become mandatory against gangsters who are ethnic citizens of the German Reich, and this could happen in the present situation, a corresponding application is to be sent to my hands. I will submit these application to the „Höherer SS- und Polizeiführer West“ (SS and police commander district West), who got the necessary authorization from the „Reichsführer SS“. (author's note: Höherer SS und Polizeiführer - HSSPF- im Wehrkreis VI was Karl Gutenberger)

On 6th February, 1945 Ernst Kaltenbrunner, head of the safety police, addressed a fax to all superior police offices and Gestapo headquarters granting all heads and superintendents of the offices and headquarters the autonomy of decision regarding the „special treatment of workers from the East (Ostarbeiter)“, i.e. their homicide. „Special treatment“ of other foreign workers and citizens of the German Reich only required a formal agreement with the commander of the safety police (BdS) or the Höhere SS and Polizeiführer (HSSPF). Every local Gestapoleiter and Polizeiführer was now entitled to issue the command for the liquidation of „Ostarbeiter“ and to recommend „special treatment“ to citizens of the German Reich accusing them of „subversive activities“. Consequently, Gelsenkirchen was no exception and there were numerous assassinations. Only very few of them were prosecuted or got preliminary investigations in the post-war period. Among those homicides were executions of forced labourers in the „Stadtgarten“ and in the „Westerholter Wald“.

|

Fig. 5: Wehrkreis VI

After the end of the war the British occupying forces were the first to introduce investigations regarding criminal actions in connection with the assassinations of forced labourers. Besides the assassinations tortures and abuses of the forced labourers who very often had family and relatives living in the allied countries were legally pusued, as according to the Hague conventions these illtreatments were to be regarded as war crimes. The investigative results give evidence of the invariable endeavour of all accused and suspected persons to keep their responsibility as inferior as possible. Occasionally, it became evident that the German inquest officers were not really motivated to unearth some of the truth regarding the crimes committed in the last phase of the war.

The foreign victims in the „Wehrkreis VI“ (see fig.5), e.g. those of the massacre in Wuppertal Burgholz, but also those of the Essen „Montagsloch massacre“ as well as all those murdered in other executions, e.g. in „Westerholter Wald“ in Buer or in the „Stadtgarten“ of Gelsenkirchen were among the victims of the special right of the police to exert „special treatment“. The delinquents, all of them being „foreigners“ were to be „despatched“ (=killed) by the police. For the fulfillment of the extermination instructions given by the inspector of the safety police (IdS), Obersturmbannführer Dr. Albath, special court sentences, court-martials or the call of special committees or police summary court-martials were neither provided for nor necessary.

From the culprit's perspective i.e. from the point of view of the defence lawyer of the accused the „invention“ of a drumhead court-martial was the only legal possibility to avert a criminal prosecution. If they could prove that the executions were court-ordered after due processes of law, a sentence on the grounds of illegal executions had to be fended off. Ironically it was Dr. Walter Abath who „invented“ the affirmation of court-martial proceedings. He, who had issued the command regarding the decentralized system of „special treatments“.

|

|

|

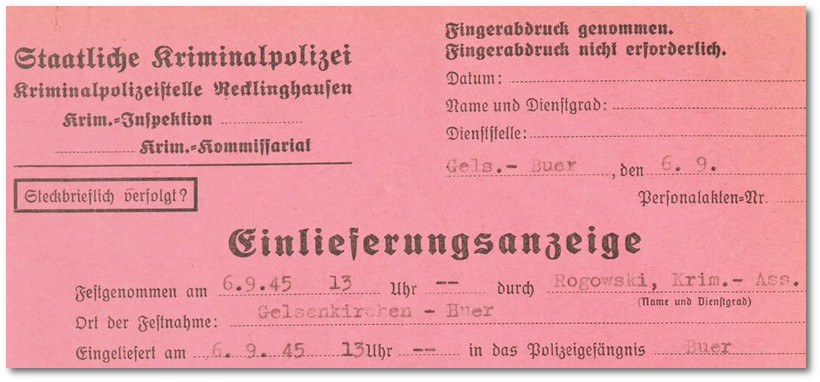

Fig.6: note of detention (Einlieferungsanzeige). First accused and offenders were arrested in the police prison of Buer – for many victims one of the places standing at the beginning of their way to their destruction in Nazi tyranny.

Numerous persons accused of comparable war crimes referred to those alleged court-martial sentences in the post-war period. By decree of 15th February, 1945 so-called drumhead court-martials could be set up in the various districts, if these felt „threatened by the enemy“.By regulation, those court-martials had to be manned as follows: one fully-qualified judge, a member of NSDAP, an officer of the German Air Force and an officer of Waffen SS (Combat SS) or a police officer. By reason of the criminal law only a plaintiff could be the prosecutor of the case. The British investigators, however, drew quite rightly the conclusion that such court-martials had never existed and would never have worked but instead court-martials had only existed within the army, SS or the police ( on territories not occupied by the Germans).

|

„Maltreatment or deportation for the purpose of forced labour or any other purpose of members of the civilian population of occupied territories or any other civil persons are war crimes and crimes against humanity“ (Nuremberg Prozess 1945/46).

|

An anonymous tip-off rendered by a citizen to the law enforcement authorities referring to an internet publication dealing with the execution of forced labourers in Westerholter Wald (forest close to the town of Westerholt) back in 1945, resulted in the institution of preliminary proceedings in 2016. Following my inquiry concerning the current state of investigations in June 2018 Senior Public Prosecutor Mr. Andreas Brendel, head of the Dortmund-seated „Zentralstelle im Lande Nordrhein-Westfalen für die Bearbeitung von nationalsozialistischen Massenverbrechen“ ( in charge of the handling and processing of NS mass murder and crimes) informed me that „judicial proceedings in this matter chaired by the department of public prosecution Essen (Staatsanwaltschaft Essen) had been closed on 09th June, 1961.“ A resumption of checking the circumstances of the closing of the matter at the time resulted in the following statement given by Senior Public prosecutor Brendel:“ There were no proofs or clues that the executions show the signs of or are to be characterized as willful homicides. As by today's law preliminary prosecutions can only be opened in cases of (premeditated) murder (and not manslaughter), I had no motive for a revision of the lawsuit of the Staatsanwaltschaft Essen (department of public prosecution, Essen).

In light of this I decided to get access to the criminal files referring to the judicial proceedings in the archive of Northrhine-Westphalia and evaluate them. The main perpetrators of the mass executions of forced labourers of both sexes in the „Westerholter Wald“ northeast of the city centre of Gelsenkirchen-Buer, Polizeisekretär Walter Marx (Gestapo branch office Gelsenkirchen-Buer) and Polizeidirektor (marshal) Otto Noack (Kriminalinspektion Gelsenkirchen-Buer),got a life term sentence after the end of the war pronounced by a Soviet Military Court, among other delicts because of the shooting of eleven forced workers (7 male 4 female) in the Westerholter Wald on 28th March, 1945. Noack was under arrest from 1945 to 1955, Marx served his sentence from 1947 until 1955. Marx on top of the above took seven forced labourers to their execution by hanging to the execution place of the concentration camp Niederhagen and confessed he had hanged a forced labourer by his own hand; the latter execution took also place in the Westerholter Wald.

The bodies of the murdered male and female forced labourers were recovered a few days later after the massacre in the Westerholter Wald and according to information given by the“ Institut für Stadtgeschichte Gelsenkirchen (ISG)“ were burried on the central cemetery Buer (Hauptfriedhof Buer). The official lists in the archives for war graves do, however, not give any corresponding evidence, as Dr. Daniel Schmidt (ISG) found out.

|

The wilfull killings portrayed in this report belong to a whole series of crimes committed in the final phase of the war in the urban area of Gelsenkirchen, including executions of forced labourers in the „Stadtgarten“, the shooting of jewish female forced workers who had found shelter in hospitals in Gelsenkirchen-Horst and Gelsenkirchen-Rotthausen after the bomb attack against the Gelsenberg Benzin AG (a refinery), who were collected by Gestapo and were shot – locality unknown. Including also the shooting of an engineer of the „Deutsche Eisenwerke“ in Bulmke by bullet of Johannes Mehrholz, a „Volkssturm-Mann“, shootings of female forced labourers in Horst, shootings on the cemetery „Am Stäfflingshof“in Schalke and also the murder of the British pilot Norman Coatner Cowley in Buer, who, after he had survived the crash of his aircraft safely, was clubbed to death by members of the so-called „Volksgemeinschaft“ (ethnic German community). This enumeration of crimes makes no claim to be complete, as there is no chance whatsoever to determine the real number of forced labourers, concentration camp prisoners, NS dissidents, opponents of the regime that have been murdered by Gestapo during the final phase by means of the „Sonderbehandlung“ (special treatment) in Gelsenkirchen alone.

The „Stolperschwelle“ (memorial brass plate) that will be installed by the sculptor Gunter Demnig in front of the head office of the Gelsenkirchen-Buer police in May 2019 (as per today's planning) is being financed by donnations. Our thanks go to Klaus Brandt, Martin Gatzemeier, Bettina Peipe, VVN BdA Gelsenkirchen, Die Linke KV Gelsenkirchen, Gelsenzentrum e.V. Gelsenkirchen and Lothar Swiderski. They made the installation possible.

Translation: Claudia Thul, Projektgruppe STOLPERSTEINE Gelsenkirchen. Februar 2019.

|

↑ Top

|

|